CHARNEY HALL Inter-School Matches

We didn’t particularly prepare ourselves for them. But yes, for cricket there was practice in the nets for bowlers and batters alike, but in the mid 1950s, apart from occasional goal kicking by the talented few who were good enough to take penalties, football skill was self-taught and improved by playing on the field.

Match tactics were yet to filter down from the professional game although we sensed that team Rossall on the Fylde coast had a distinct advantage as they had Stanley Mathews as their part-time coach. Their game appeared more skilful and from the outset seemed to be skewed to their advantage. We were easily outwitted and I doubt that we ever won playing against them in my time.

Reports of matches were duly filed by Maxwell Duncan or Raymond Hirst in the folder for the Charney Hall Notes which was published each year, and school colours were awarded after the match if any boy excelled.

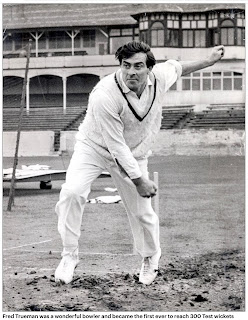

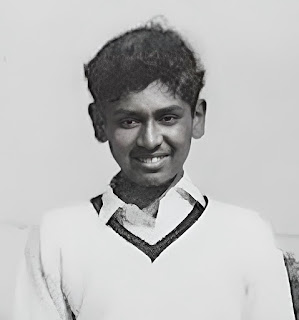

Some pupils were outstanding, Sandy Walls our centre forward, Bernard Swift our fast bowler come immediately to mind. Bernard’s run-up was as long as the pitch! As he released the ball it curved towards the intrepid batsman accompanied by a fluttering sound as the spin imposed upon it rounded on the wicket. You may recall that in another post I describe the carnage that fast bowling had the potential of inflicting on the poor wicket keeper if, God forbid, an edge was found on the bat! These boys were our secret weapons and we relied upon them to save the day if there was any chance of losing.

I sensed that I would gain my colours eventually by default. My speed down the left wing of the football field was a distinct advantage but I had to master the art of taking the ball with me and providing, with my left foot, a consistent supply of crosses and ‘corners’ to the forwards waiting in the centre of the field. That simple task appeared to evade me time and time again.

Matches all seemed quite a light hearted affair but by the time our coach had passed the stone gateposts framing the entrance to the opposing team’s school drive or we heard the drumming sound of the visiting school coach’s diesel engine, the rumblings of pre-match nerves could be felt in our stomachs!

In football it was the first kick by a centre forward that released the tension. In cricket, if Charney were batting first, nerves were stretched until the first ball of your innings was balled. It was best just to try and relax and enjoy the day, after all it was better than lessons!

Our football pitch sloped across its width down to the limestone retaining wall which bounded Charney Road - it is still there as straight, high and true as it was in 1953 when I first saw it as my parents drove me for my first unsolicited hours at Charney Hall School.

The slope was graded so it was deliberate, probably to take up the difference between cut and filled levels which could not be resolved in any other way. After prolonged rain the pitch could become quite soft, especially along the lower boundary. The new tan leather football, dutifully provided at each school match, was beautiful, inexplicably small in appearance and was inordinately heavy and excruciatingly painful to kick. So much so that Sandy Walls took to scoring goals with the blunt toe of his boot. Heading the ball was like being struck by a rock... Kicking the ball with the top of the foot produced an excruciating, stinging sensation which made us think twice about kicking it again. We could have faired much better if they had provided something that was a pleasure to kick...

At the final whistle we all returned to the dressing rooms situated in the new block which had been built behind the old buildings, overlooking the cricket field. Knees, shorts and long socks were muddied, and dubbined leather boots with original leather studs were filthy and clogged around the studs with grass clods from half the pitch.

The bath, more like a large rectangular, ceramic tiled tank, was sunk into the concrete of the changing room floor. It was full of piping hot water....but it was the visiting team’s prerogative to use the bath first as the water was not replenished after use. When our turn came the colour had changed from a clear swimming pool aqua to an opaque muddy brown! Even so a post-match bath was a unique experience. Either celebrating a win or commiserating each other on account of a loss, became a delight and always eagerly anticipated as the hot water left our bodies rejuvenated, feeling warm, relaxed and fresh after a hard match.

A cricket match was more gentile, less physical. Time seemed to pass more slowly, perhaps because matches were longer, and we were bathed in warm sunny days followed by spectacular sunsets. Pressed ‘whites’ were compulsory and we had to apply whitening to our leather soled, canvas topped shoes to cover the green grass marks made in the last match. I liked the smell of the ‘blanco’ and it was linked inextricably in my mind with the smell of linseed oil, freshly cut grass and the sweet air of Morecambe Bay. Some fast bowlers caught and tore the canvas toes with the steel studs which were screwed into the soles of each pair of shoes. A bodged repair was quickly carried out with blobs of ‘blanco’. Trouser ‘whites’ also acquired a dull red patch at the top of bowlers’ legs where polishing took place in order to improve the spin of the ball. Most boys had green marks on the trousers made by ducking or diving after errant balls. Wearing a cream white cap with maroon octagonal segmented ring was a privilege and worn with pride - visible proof of your cricketing prowess and possession of the school ‘colours’.

Both cricket and football fields were freshly marked with lime wash before each match - sometimes very precisely by Raymond Hirst. Charlie and Herbert, the groundsmen/gardeners, ensured that the grass was freshly cut and the cricket square was levelled by selected pupils with a large ‘gang’ roller - a team effort. The white painted boarded sight boards were rolled into position on opposing boundaries, on their small cast iron wheels and into position dead centre of the wicket.

The preparation and ‘breaking in’ of a new cricket bat was carried out in preordained, classical tradition. Layers of linseed oil were applied over the willow blade (Salix Alba var. caerulea for those who are interested). Thereafter a leather bound cricket ball was used to ‘break in’ the bat. This was often undertaken in the school holidays as it was most probably then that the new bat had been acquired. In my time it became fashionable to have a string binding about 1/4 way up the bat, this presumably prevented the bat from splitting but it looked very professional - for my instrument a rare, almost improbable event.

Len Hutton can be seen below with a Gradidge bat. The manufacturers knew that his name would sell their products, especially to young boys who were oblivious to the burgeoning power of marketing.

Schoolboy Heroes (in no specific order):

Cricket: Len Hutton, Denis Compton, Jim Laker, Peter May, Freddie Trueman, Frank Tyson.

Comments