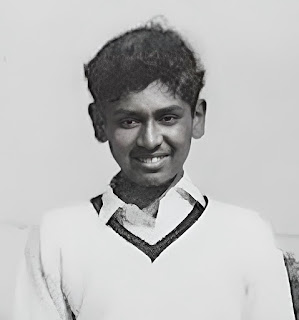

CHARNEY HALL James Harold Innes Hopkins

The classroom door was located just on the right, at the entrance to the small courtyard, adjacent to the Master’s Common Room. He taught us, more kept watch over us, as we copied identical lines of a single sentence that he had written in chalk on the blackboard in the copperplate style.

He sat, with pale, gaunt face which featured an aquiline nose, hollow eye sockets punctured with pale blue grey eyes, and seldom moved for the entire lesson. His slim suited frame and boney blue veined hands remained poised over the master’s desk, which was, if I remember correctly, located on a raised wooden dias alongside the blackboard, at the front of the class. Little was uttered, for no words were required, as we knew by his demeanour that he would not tolerate any nonsense!

The lesson felt more like detention and we looked forward to resting our ink stained fingers at the sound of the school bell. I was left-handed like my mother before me and was not particularly interested in changing my ways, unlike my mother who was forced to swap hands. Thus I shot myself in the foot because I was unable to use an itallic pen in a later calligraphic life as where the script demanded a thick line, I could only muster a thin line and visa-versa.

So I had to put up with the ‘pushing’ instead of ‘pulling’ of the nib across the sheet of paper, which could at any time be accompanied by the unpredictable stalling of the steel nib on any imperfections, guaranteed to propel a shower of ink droplets across my spidery script.

A sheet of blotting paper was always close to hand. Large round blobs of ink which threatened to run across the paper could be best absorbed by using the corner of the blotter to avoid total disaster. Some may recall that the pen was recharged from the inkwell, a white ceramic pot with concave top, recessed in the right hand corner of the grooved oak top of each desk.

At the end of the lesson both my inky index finger and thumb had a deep impression of the metal ferrule of the nib holder impressed into the skin, such was my concentration in attaining the correct right-handed slant and articulation of each letter.

This desk is in remarkable condition!

The school desks were something else in the 1st form. Being without doubt the oldest in the school, the tops were lovingly carved by all the miscreants who had occupied those seats in the past. Carved at random and extending from top to front edge of the angled top, I could put faces to names with reference to the schoolboys’ mug shots which lined the dining room walls along the dado rail. Almost every boy had a penknife. Some were given out as bribes by pupils whose fathers had businesses that must have benefitted from such a strange gift. But now I knew what their true use was….

Mr Hopkins majored in and taught Latin and sometimes Greek for those who were intelligent enough to take that option. However for us Mr McCullagh and later Lennox Aitchison would acquaint us with the finer points of the Cambridge Latin Entrance Examination - amo, amas, amat, amamus, amatis, amant....’amo’ I believe was the first verb that we conjugated, soon to be followed by the future tense - amabo, I’manass, I’m a rat etc...

Now with benefit of the England Census which facilitates research into family ancestry we can accurately calculate Mr Hopkins’ age to be 79 at the time, a prehistoric number - No wonder he looked so ancient to us eight year olds!

It has also been possible to reveal some tantalising details of his family history….

His great grandfather William Randolph Hopkins was of Irish descent and lived in the town of Thurles, Tipperary. He was an officer of the Inland Revenue of Ireland.

His grandfather, John Castell Hopkins, had emigrated from Ireland and had amassed a fortune in a lifetime of productive work through investment in collieries and the burgeoning railway system in the north east of England.

He was elected onto the first Board of Directors of the Great North of England Railway Company and was involved in the Stockton and Darlington Railway, the Weardale Extension, the Wear and Derwent Lines.

In 1845 he became a director of the Wear Valley Railway. Further appointments followed :

1. Vice chairman of Stockton and Darlington Board of Directors.

2. Director of the Middlesbrough and Redcar Line (1841)which merged with The Stockton and Darlington System (1858).

3. Admiralty Commissioner on the Tees Conservancy Commission.

4. Partner of Hopkins, Gilkes and Co, Ironmasters of Middlesbrough-upon-Tees.

He had two wives due to his first wife’s early death in August 1816, perhaps in childbirth, and given his 8 children a good start in life. They in their turn had provided him with over 50 grandchildren, one of the youngest being James Harold Innes Hopkins, the oldest being some 33 years his senior.

James’s father, James Innes Hopkins married Charlotte Stephens at St. Peter’s Church, Dublin on 11 March 1863. When single he lived in Southfield Villas, Middlesbrough and was registered as an ironmaster at 23. By 1871 the family had moved south to The Poplars, Fassett Road, Kingston-upon-Thames and there were already 6 children, one (unnamed, but soon to become Elise Hopkins) was under 1 month old.

James Harold Innes Hopkins was born 3 years later in affluent Kensington, London on the 5th February 1874.

When James was baptised on 18 March 1874 at St Stephen’s Church, Kensington, the family had moved to 3 Southwell Gardens, Kensington. Unfortunately a family tragedy was imminent as his father (36) was to die 2 months later in Paris, leaving his 40 year old widow Charlotte to bring up their 7 children without a husband’s support. He was on his way back from Pau, just north of the Pyrenees where he had sought rest and the clean mountain air. These measures indicate that he may have been suffering from consumption.

The Hopkins’ neo-classical town house was a substantial investment being 3 bays wide with entrance portico, having 5 principal floors, an attic and full height habitable basement accessible by means of an external staircase from the front pavement - a total of 7 storeys high! There appears to have been the bonus of a 2 storey mews block within the curtilage, at the bottom of the rear garden.

In 1875 James Innes Hopkin’s probate affidavit (no attempt at perverting the wrath of HMR here) indicated that his effects would not exceed in the region of £5,000,000 (at today’s costs).

By 1881 the census* confirms that Charlotte (46) had moved with her family to Somerville Cottage, Sydenham, her husband’s untimely death perhaps prompting the move from Kensington. She had a 49 year old companion Matilda Elverton living in the house as well as a domestic servant Jane (16) from Sussex.

Ten years later the 1891 Census indicates that Charlotte Hopkins was now 57yrs old and was living at 4 Northumberland Villas, Sydenham. At that time her 5 children, John (26), Charlotte (25), Minnie (24) , Elise (20) and James (17) were still living at home at the same address. The census records that Charlotte was ‘living on her own means’, an indication that her husband had ensured that she could live an independent life. Her son John was a clerk in a stockbroker’s office and the 3 daughters were governesses. Young James was the only scholar.

By 1901 the 27 years old James Harold Innes was one of 4 Assistant Masters at Hinwick House Preparatory School for Boys, Podington, Bedfordshire. There were 23 boarders whose parental homes were scattered around Britain as well as Canada, the USA and Singapore.

By 1911 James, now 37, had become a partner at the school. The headmaster, his colleague was George W Gruggen, a married man, originally from Chichester, who was also his landlord. It is recorded that he lived within the school complex in a single room.

During the so-called Great War, WW1, James lost his uncle, Capt James Randolph Innes Hopkins and 2 cousins (once removed) Lieut. Castell Percy Innes Hopkins and Charles Randolph Innes Hopkins, both sons of Charles H I and Helen Hopkins. It is well documented that Edwardian officers led the charge out of the trenches from the front and that they had paid the price for their bravery.At some point James left Hinwick and the next we hear of him is in the 1939 England and Wales Register, taken just before the Second World War when he is recorded as a master at Charney Hall aged 65.

Maxwell Duncan and Raymond Hirst were the headmasters and they had already purchased the school off Mrs Conrad Podmore in February 1937. Whether James H I Hopkins had been employed previously at the school by the Podmores is not clear.

The 1939 Register recorded that one Arthur B K McCullagh, aged 13, was also a pupil at Charney at the same time.

So fast forward to September 1953 when we first encountered the 79 year old Mr Hopkins sitting behind his desk in the first year classroom, in our very first term at Charney Hall School. We knew nothing about the life that this old man had endured up to that point in time, the traumas that he may have suffered and the extent of knowledge and life experience that he had accumulated. Least of all we were ignorant about his family connections and the amazing contribution that his forebears had made in the north east of England.

This was quite normal in private schools as masters didn’t necessarily live locally to the school and were not generally known personally by parents. Masters very rarely referred to life in the outside world.

But James Harold Innes Hopkins could trace his ancestry through his grandmother, Jane Innes, directly back to the Dukes of Roxburghe in one generation and to the magnificent Grade 1 listed Floors Castle at Kelso. Indeed his grandparents had been married there.

When he retired to Bath he lived, by our modern standards, in a large , semi-detached Georgian house, no. 5 Springfield Place, until his health failed him. He died on 31 December 1958, aged 84 at the Landsdown Grove Nursing Home (now a hotel), just 200 metres down the road, only 4 years after leaving Charney.

Through my researches about his life and family I have come to the conclusion that James Hopkins lived solely for one purpose. That was, the imparting of knowledge to a younger generation of scholars through the practice of teaching. Nothing else appears to have mattered. His personal comfort and lack of material possessions did not seem to have concerned him. An almost monastical concept that some would say was a world away from the trivial, immaterial materialism of today.

Even in the 1950s, after the austerity of WW2, an interest in acquiring new fangled kitchen appliances, television sets and flamboyant cars displaying the influence of American designers, was taking hold. The change was inexorable and he must have been aware of it, even in the slow ebb and flow of life in a private school.

In retrospect, his life represented a link, a window with a view into the past, spanning both World Wars, the Edwardian and Victorian eras, reaching almost to medieval times, well before the wheels of the second industrial revolution (or is it the fourth!?) had chance to turn and kickstart the digital age.

For these reasons alone he deserves our respect and admiration, however much we may have questioned the futility of a dead language and hated all the subjects that he taught!

The Hopkins Family records go back to 1548 and the family was awarded a Grant of Arms in 1661. Their motto is “Suavitate aut vi” which is translated “ By gentleness or force”. I suppose that implies that we could not have won either way….

*When researching each 10 year census I noted that whereas most of the male heads of families described themselves as ‘labourer’, ‘groom’, ‘servant’, ‘gardener’ or even ‘headmaster’ or ‘assistant master’, many of the male line of the Hopkins family and others would refer to themselves as ‘gentleman’. A gentleman I have learnt is a man with independent means, that is, one who does not need to work for a living! Although this status occupies the bottom rung of the former ‘Upper Class’, it doesn’t seem too bad a place to be to me !

Comments